Indonesian regulation puts environment and health at risk by declaring palm oil waste and coal ash non-hazardous

He is about to end up run over, his mother saves himThe recent decision by the Indonesian government to remove from the local environmental activists is of great concern hazardous waste list a powdered clay used to lighten palm oil.

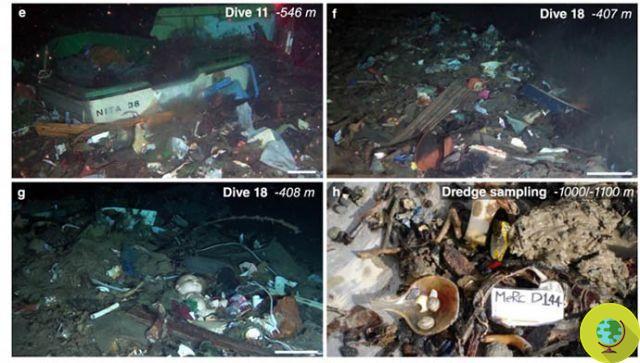

Environmentalists fear, on the one hand, a drastic loosening of environmental protection mechanisms and, on the other hand, a dangerous and inefficient management of waste, related to a probable increase in episodes of illegal disposal of untreated waste in landfills or near residential areas.

The recent "delisting" of some hazardous waste by the government of Jakarta is the result of years of pressure exerted by large Indonesian companies, which consider the treatment of that type of waste too expensive in terms of costs and therefore ask to be authorized to sell some solid waste obtained from the bleaching process ofPalm oil - notice as exhausted bleaching earths (from the English acronym SBE: Spent Bleaching Earth) - to cement producers and the construction industry.

The government regulation, issued by the Indonesian executive last February 2, not only removed SBE from the list of hazardous waste, but also removed from the list the ash residues resulting from the combustion of the carbon.

Index

SBE: toxic or non-toxic?

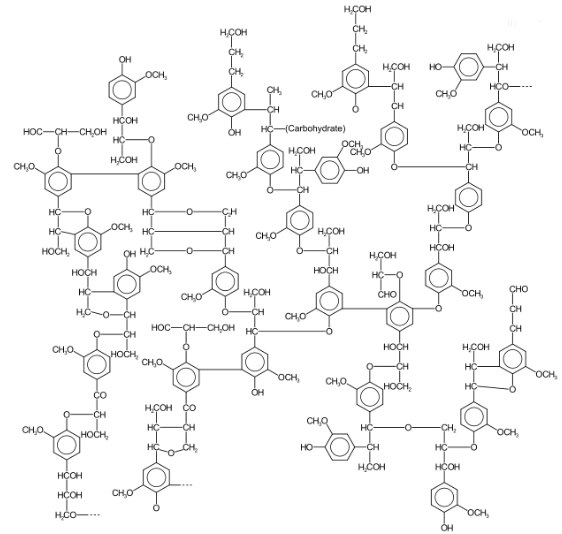

Indonesian industry uses large quantities of a clay powder, called spent bleaching earth or SBE, to improve the clarity of palm oil and remove any odors. Once the refining process is complete, the SBE retains a certain amount of residual oil - up to 40% of the total - and must be disposed of carefully to prevent it from entering the ground or water table or catching fire.

Since 2014, SBE had been classified as hazardous waste and specific protocols had been prepared to allow for its correct treatment and disposal. Last February, however, the government turned around and declared that SBE with a residual oil content of less than 3% can no longer be associated with hazardous waste.

This change in strategy is by no means without consequences. As noted by Nur Hidayati, executive director of the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi) - the country's most important environmental NGO - the new legislation seems to legitimize less monitoring of the performance of the Indonesian palm oil industry, a sector in which Indonesia leads the world.

What risks are there

The further risk is that Indonesian companies feel more free to dispose of SBE with a residual oil content higher than the 3% limit set by the regulation precisely because of the concrete monitoring difficulties in the field.

This eventuality would expose the country to serious problems, because an unreliable amount of toxic and dangerous material could be released into the environment without a preventive and widespread control and without the active participation and the right to information previously reserved for local communities and Indonesian civil society.

The Omnibus law, in fact, contrary to the previous environmental statutes, provides that only the communities directly concerned can have a voice in theenvironmental impact analysis, cornering environmental NGOs and other similar bodies committed to environmental protection and the protection of indigenous peoples.

The challenge of the Omnibus law

The government's move is part of a broader plan deregulation and administrative simplification, sanctioned by a controversial legislative act approved on 5 October 2020, in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, in order to attract foreign investments and revive the economy and the world of work.

Indonesia's President Joko Widodo, in his second term, applauded the approval of the legge Omnibus on the creation of new jobs, which nevertheless sparked a wave of mass protests, promoted by workers' unions and numerous civil society organizations.

Strongly criticized by environmental activists, human rights and land rights defenders and local indigenous groups, the law would have deliberately dismantled all forms of environmental protection to further the interests of the palm oil industry, mining multinationals and corporations. that produce the "dirty" energy of coal and fossil sources.

An act that, in their opinion, not only legitimizes the systematic destruction of nature, but also intends to undermine the very existence of the traditional communities that rely on that nature to survive.

Addiction to coal

As mentioned above, the Indonesian government has proceeded with the same regulation to declare fly ashes and bottom ashes are also not dangerous produced by the combustion of coal, residues that contain chemical compounds harmful to human health and the environment, such as mercury, arsenic, lead and chromium.

A measure that has been described as a capitulation of government authorities to thecoal industry, which has long been waiting to receive the authorization to freely sell the ashes to cement producers, bypassing the onerous requirement of waste treatment.

Font: Nikkei Asia/Mongabay

Read also:

Palm oil is still a huge problem (and hides abuse, violence and child exploitation)

Palm oil and cellulose: Indonesia is burning (VIDEO)

Palm oil: this is how Indonesia is burning and polluting. And because it's everyone's problem (PHOTO)