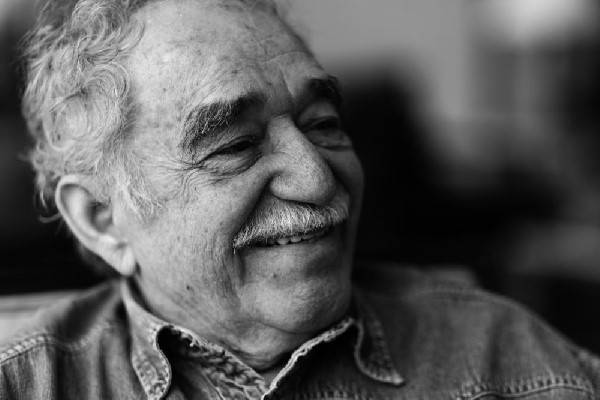

The Buendía Generations of Florentino's One Hundred Years of Solitude to Boundless Love in Love in the Time of Cholera, the case of Chronicle of a death foretold: who was Gabriel Garcia Márquez.

He is about to end up run over, his mother saves himNobel Prize in 82 and maximum exponent of the so-called magical realism, Gabriel Jose de la Concordia Garcia Marquez, to the century "Gabo”, He is much more than a writer. Inspired throughout his career by Jorge Louis Borges, Faulkner, Juan Rulfo, Virginia Woolf and Vargas Llosa, Marquez - Colombian naturalized Mexican - became without too much difficulty the main representative of Latin American literature of the sixties and seventies. And not only that: Gabo strongly challenged the death penalty, supported disarmament and denounced the US drug crackdown.

He was responsible for the most beautiful pages of the twentieth century: from the history of the Buendía generations in One Hundred Years of Solitude to the boundless love of Florentino in Love in the time of cholera, passing through the case of Cronaca di una morte announced.

Gabriel Garcia Márquez cannot fail to be read, if only his flowing style is often crossed by a bitter irony, by intertwining between reality and fantasy and from the background history. It is no coincidence that Márquez has also made himself a spokesperson for struggles for freedom and justice.

Index

Gabriel Garcia Márquez biography

Photo source

Gabriel Garcia Márquez was born to Gabriel Eligio García, telegraphist, and Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán, on March 6, 1927 in Aracataca, a small river village in northeastern Colombia, but was raised in Santa Marta by his grandparents, Colonel Nicolás Márquez and wife Tranquilina Iguarán.

From his maternal grandfather, a liberal politician and veteran of many wars, and from his grandmother, a psychic, Gabo has always been very influenced. The former is often found in his militaristic figures in novels such as La mala ora (1966), L'autunno del patriarca (1975) and Nobody writes to the colonel (1958). And even the grandmother Tranquilina, who made her miraculous stories and ancient legends, is always present also among the pages of Márquez, who thanks to her changes everyday life into a series of supernatural events. She, Tranquilina, lived in a world of her own of ghosts and superstitions, where the living and the dead coexisted peacefully, and she will undoubtedly lead to Magic realism which will later make Márquez's fortune.

Once his grandfather died in 36, Gabriel moved to Barranquilla where he graduated ten years later at the Colegio Liceo de Zipaquirá.

In 1947 he began his studies at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotà at the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences (and then abandoned it) and in that same year he published his first short story La tercera resignacion in the magazine El Espectator.

In 1948 he moved to Cartagena where he began working as a journalist for "El Universal" and as a collaborator of other American and European newspapers, while at the same time joining a group of writers dedicated to reading the novels of authors such as Faulkner, Kafka and Virginia Woolf .

In 1954 he returned to Bogotà as a journalist for "El Espectador", when he published the story Dead leaves, then again the following year he lived for a while in Rome for a few months, where he began to attend directing courses, and then moved to Paris. In '58 he married Mercedes Barcha, the love of his life, and from that marriage Rodrigo and Gonzalo were born.

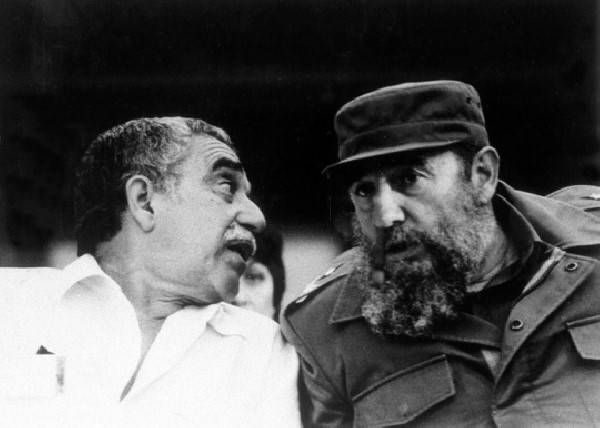

With the rise of Fidel Castro, Gabo goes to Cuba and start collaborating with"Prensa Latina" agency founded by Castro himself, but he soon moves to Mexico City due to constant threats from the CIA and Cuban exiles. Here he wrote his first book The Funeral of Mama Grande, while in 1967 he published one of his best-known novels, “One Hundred Years of Solitude”, the events of the generations of the Buendía family in Macondo. A work that is considered the maximum expression of the so-called magical realism.

This masterpiece is followed by The Autumn of the Patriarch, Chronicle of a Death Foretold, Love in the Time of Cholera and in 1982 he is awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. In 2001 he suffered from lymphatic cancer. In 2002, however, he published the first part of "Vivere to tell it", his autobiography of him and in 2005 he returned to fiction by publishing the novel Memory of my sad whores, his latest novel by him.

Gabo died on April 17, 2014, at the age of 87, in a clinic in Mexico City.

Márquez, the magical realism between loneliness and a sense of death

Márquez's vocation is since his youth for writing: to live he begins to be a journalist but he would like to become a novelist right away, knowing that he wants to tread a style that is not realistic but the one with which his grandmother told about ghosts.

While collaborating with Prensa Latina, Fidel Castro's news agency born after the Cuban revolution, the young Márquez wants to stay well away from the world of politics. Openly critical of dictatorships and violations of human rights (after Pinochet's coup in Chile he declares that he "does not publish" and one of his most famous texts, Notizia di un sequestro, from 1996, tells the story of ten hostages kidnapped by Pablo Escobar's drug traffickers), Gabriel always tries to avoid getting involved in the affairs of the Cuban revolution.

Photo source

Rather, he dedicates his writings to the miserable appearance of men, to war and abuses with a style linked to South American nature and that magical realism that puts poetics halfway between the magical, surrealist element and the realist representation. Márquez declares that he limited himself to telling in his novels things that have already happened, but the influence of the psychic Tranquilina and that one is strong and clear.effect of "estrangement" through the use of magical elements, described equally realistically.

The "Real Wonderful"Is therefore very much in evidence in Márquez, it is no coincidence that he is considered the greatest Latin American exponent, and reproduces a microcosm in which the dividing line between living and dead is not clear at all, helping to completely isolate the story from the rest.

A famous example of this is, in One Hundred Years of Solitude, the magical scene of the ascent into heaven by Remedios the beautiful, which disappears from the sight of the family while folding the sheets and which is actually inspired by something that happened: a friend of Márquez's grandmother, ashamed to admit that her daughter had run away with a man, had said that the girl had been hired into heaven in his presence.

Gabo's writings are not just one reflection on life and its ironic episodes, but also on the slow and inexorable passing of time and death, which represents a constant presence in his writings. Furthermore, his characters are picturesque and at times ridiculous, but they are basically only. Alone in the face of an inevitable death and in the face of life, which for Gabriel García Márquez seems to be a continuous reflection of his end, with its ghosts that do not torment the living, but speak to us to chase away loneliness.

No wonder then that Gabo always stands out for his aversion to death and his desire to observe life beyond the end, for that mystery and that doubt that essentially run through his entire work. For Márquez, death is the greatest injustice and this is most likely the reason why the ghosts who converse with his characters are sad.

“Write a lot,” Gabo will say. It is the only antidote to avoiding the worst.

Gabriel Garcia Márquez, the famous phrases

Photo source

Photo source

You can be in love with several people at a time, and all with the same pain, without betraying any, the heart has more rooms than a brothel.

(Love in the time of cholera)

All human beings have three lives: one public, one private and one secret.

(Live to tell it)

The problem with marriage is that it ends every night after making love, and it has to be rebuilt every morning before breakfast.

(Love in the time of cholera)

I realized that the invincible force that moves the world is not so much happy love, but unrequited love.

(Memory of my sad whores)

Nothing tells more than a person about the way they die.

(Love in the time of cholera)

When a woman decides to go to bed with a man, there is no obstacle that she does not overcome, neither strength that she does not break down, nor moral consideration that she is not willing to put aside: there is no God who is worth.

(Love in the time of cholera)

It is not true that people stop chasing dreams because they get older, they get old because they stop chasing dreams.

It happens that you touch someone's life, you fall in love and decide that the most important thing is to touch it, live it, live with melancholy and anxiety, get to recognize yourself in the other's gaze, feel that you can no longer do without it ... and what Does it matter if to have all this you have to wait fifty-three years, seven months and eleven days including nights?

(Love in the time of cholera)

The secret to aging well is to have made an honesty pact with loneliness.

(A hundred years of loneliness)

A man knows when he is getting old because he begins to look like his father.

(Love in the time of cholera)

He was still too young to know that the memory of the heart eliminates bad memories and magnifies good ones, and that thanks to this artifice we can tolerate the past.

(Love in the time of cholera)

You don't die when you have to, but when you can.

(A hundred years of loneliness)

Nothing in this world was more difficult than love.

(Love in the time of cholera)

She slept without knowing it, but knowing that she was still alive in her sleep, that half the bed was too many, and that she lay sideways on the left edge, as always, but that she lacked the counterweight of the other body on the other side.

(Love in the time of cholera)

It is easier to start a war than to end it.

(A hundred years of loneliness)

I am about to turn XNUMX, and I have seen everything change, even the position of the stars in the universe, but I have not yet seen anything change in this country.

(Love in the time of cholera)

Give me a bias and I'll lift the world.

(Chronicle of a death foretold)

There is no sadder place in life than an empty bed.

(Chronicle of a death foretold)

Sex is the consolation that comes when love is not enough.

(Memory of my sad whores)

She never pretended to love or to be loved, even though she always had the hope of finding something that was like love, but without the problems of love.

(Love in the time of cholera)

She was convinced that the doors had been invented to close them, and that curiosity about what was going on in the street was a woman's thing.

(A hundred years of loneliness)

The only thing worse than bad health is bad fame.

(Love in the time of cholera)

A casual glance was the origin of a cataclysm of love which half a century later was not yet over.

(Love in the time of cholera)

The world moves forward. Yes, I told him, it moves forward, but circling the sun.

(Memory of my sad whores)

It is impossible not to end up being what others believe one is.

(Memory of my sad whores)

But he let himself be carried away by his belief that human beings are not always born on the day their mothers give birth, but that life still forces them many more times to give birth by itself.

(Love in the time of cholera)

Nobody teaches you life.

(Love in the time of cholera)

No fool is crazy if you fit his reasons.

(Of love and other demons)

The ideas belong to no one, "he said. He drew a series of continuous circles in the air with his index finger, and concluded: “They fly around there, like angels.

(Of love and other demons)

There is no medicine that heals that which does not heal happiness.

(Of love and other demons)

Germana Carillo